top of page

The Challenge of Understanding Art in Museums – Choosing Your Path with Gaudio

When planning to visit a museum, one usually expects to get to know the exhibits and the artifacts. In an art museum, one hopes to meet...

Feb 4

The Nuanced Architecture of AI in Museums & Cultural Spaces - Why Bigger Is Not Always Better

Discover how cultural institutions can responsibly adopt AI to enhance visitor experiences while minimizing environmental impact.

Jan 3

The Human Touch in Digital Spaces - How Conversational AI is Reshaping Museum Experiences in 2025

AI is revolutionizing museum experiences, turning silent masterpieces into engaging cultural dialogues through personalized digital guides.

Dec 15, 2024

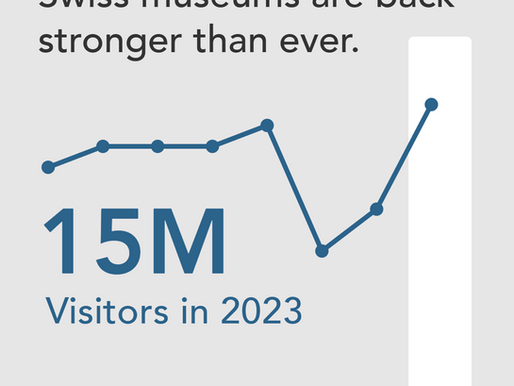

A Deeper Look at the Swiss Museums Statistics of 2023

The Swiss Federal Statistical Office’s 2023 report reveals a museum sector at a pivotal moment.

Dec 10, 2024

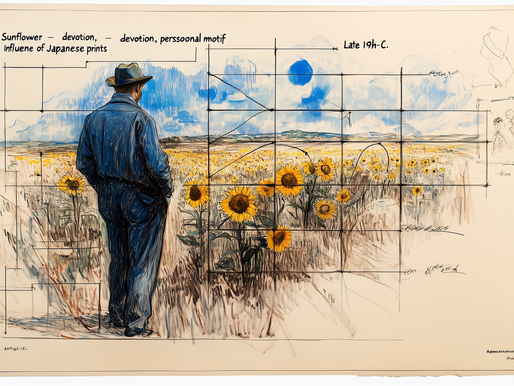

The Three Layers of Art Understanding with Artificial Intelligence: Applying Panofsky's Methodology through Gaudio

The Birth of a Methodology One of the most important art historians of the 20th century, Erwin Panofsky, introduced “Iconology” as a way...

Dec 2, 2024

Beyond Simple Personalization: Creating Dynamic Museum Experiences with Artificial Intelligence

AI revolutionizes museum experiences: From static guides to dynamic, personalized cultural interpretation.

Nov 10, 2024

The Digital Renaissance: AI's Role in Art Discovery

Exploring how AI enhances museum experiences through Panofsky's art interpretation framework, bridging traditional theory with modern techno

Nov 1, 2024

bottom of page